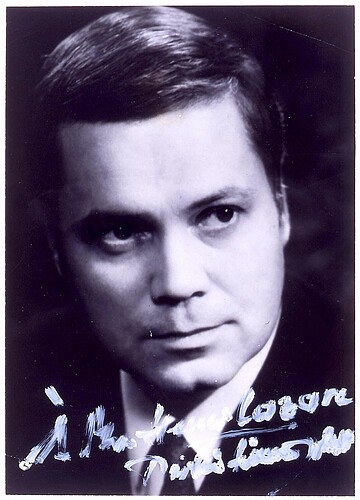

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (1925-2012), one of the most important singers of the 20th century, was born one hundred years ago. The UdK's music newsletter cannot ignore this anniversary. Fischer-Dieskau's career is closely linked to Berlin and the Hochschule für Musik, now the UdK's Faculty of Music. According to his memoirs, he was ‘successively a schoolchild, student, recruit, opera singer and university teacher’.

Fischer-Dieskau was lucky that all doors were wide open to him right from the start thanks to his great singing talent: his rise was ‘meteoric’, according to the music critic Sybill Mahlke, an observer of Berlin's post-war musical life, in a review. Is attending university even important for such a high-flyer? Or must this stage in the career of an exceptional musician be considered irrelevant? Since the 19th century, the latter assessment has been repeatedly found in literature that takes a critical look at the development of conservatoires, and Fischer-Dieskau's CV seems to support this view. In terms of the sheer amount of time he spent at university, it was only three semesters.

On closer inspection, however, things turn out differently. The unusually short period of enrolment was due to the circumstances of the time. The war was raging when the young musician enrolled at the university immediately after leaving school and studied there in the summer term of 1943. In August, however, he was pulled out of his studies, which had only just begun, and called up for military service. And it is clear to see that, despite his natural talent, the university gave him a lot to take with him. The credit for this goes above all to the professor of singing, who accepted Fischer-Dieskau into his class ‘after lengthy, persistent requests’: Hermann Weißenborn.

But let's take a closer look. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau grew up as the son of a head teacher in Lichterfelde. Even as a child, he and his mother took advantage of the opportunities to listen to concerts in Berlin, for example at the Sing-Akademie and the Philharmonie. In the Beethoven Hall, the ‘ardently enthusiastic boy’ listened to the alto Emmi Leisner from the front row. During a meeting in the artists' room, she recommended the Bach singer Georg A. Walter as a teacher, who introduced him to the world of Johann Sebastian Bach's cantatas. The budding artist already attracted attention as a schoolboy. His grammar school organised a concert for him in which he performed Schubert's Winterreise. The event took place on 30 January 1943, the tenth day of the National Socialist ‘seizure of power’ in Zehlendorf town hall in front of an audience of around two hundred people. In the middle of the event, the sirens began to wail; everyone had to go to the cellar for two hours because of an air raid.

Immediately after graduating from high school, the singer-to-be waited ‘in a huge crowd of ladies’ at the Hochschule für Musik until it was his turn to take the entrance exam; most of the men were already at war. Fischer-Dieskau performed Der Wegweiser (No. 20) from Winterreise; ‘exhausted and hungry’ as he was, he couldn't remember the words to the third verse. Weißenborn prompted him. This teacher was considered ‘a luminary among Berlin pedagogues’. But then, as I said, he was called up. He went back to the theatre with a fellow student, the cello student Irmgard Poppen, who later became his first wife; this was followed by his deployment to the Eastern Front.

Fischer-Dieskau survived the campaign in the East, went to the Italian front and was taken prisoner by the Americans. He succeeded as a singer in the prison camps. After more than two years of imprisonment, he was released in the summer of 1947. He first went to Freiburg im Breisgau, where he met Irmgard Poppen again. When he wanted to return to Berlin - to his mother and ‘to the teacher’ - he was looked at with pity: the situation in the war-ravaged city of millions seemed too desolate. And yet there was a kind of awakening there, especially for Fischer-Dieskau.

The fact that he resumed lessons with Weißenborn immediately after the war and imprisonment is the best proof of the esteem in which he held his teacher. In the winter semester of 1947/48, he re-enrolled at the Hochschule für Musik. In an interview with Eleonore Büning, he reported: "Immediately after my return, I continued working with my singing teacher Hermann Weißenborn, whose incorruptible advice I was still seeking when I had long since been on stage. I realised that mastering the technique was the prerequisite for being able to express myself as a person." The university taught him what the valid standards were. In his autobiography, he wrote: ‘Despite all the new activities that soon overwhelmed me, I continued my lessons with Weißenborn with only brief interruptions until his death in 1959’. He therefore took private lessons from his teacher after his time at the university.

Although Weißenborn was not an important singer, he was a successful singing teacher, of which Fischer-Dieskau is not the only example; the famous tenor Joseph Schmidt was also one of his students. Through his studies with Weißenborn, Fischer-Dieskau is part of the singing tradition of the Berlin Hochschule. The details of his affiliations are as follows: Weißenborn's teacher was Johannes Messchaert, a baritone from the Netherlands. He came to the Berlin Hochschule in 1911, four years after Joachim's death, and paved the way for his pupil Weißenborn to become a teacher. Messchaert had studied with Julius Stockhausen, the singer who was a friend of Brahms and who had been appointed head of the vocal department when the academy was founded in 1869. However, the appointment did not materialise. And Stockhausen in turn was a pupil of Manuel Garcia junior at the Paris Conservatoire. Fischer-Dieskau practised vocalises by Garcia under Weißenborn's aegis. Weißenborn gave Fischer-Dieskau a valuable edition of the École de Garcia (1840/1847), emphasising the school connection.

Important steps in Fischer-Dieskau's career were taken in the late 1940s: the recording of Winterreise at RIAS - the radio station in the American sector - in 1947 and, the following year, his engagement at the Städtische Oper by Heinz Tietjen, which formally ended his student days. In 1949 he was already the ‘1st lyric baritone’ at the West Berlin Opera House. At the Salzburg Festival in 1950, Fischer-Dieskau met Wilhelm Furtwängler, who was conducting the Philharmoniker again in Berlin. A brilliant career as a lieder, concert and opera singer began.

More than thirty years after his student days, Fischer-Dieskau returned to Fasanenstraße. The Hochschule der Künste was able to recruit him as a teacher: Following a suggestion from Department 9 - Performing Arts - he was appointed in 1981 and took up his post at the beginning of 1983. He now held a professorship for singing and song accompaniment. As agreed, lessons took place in block courses, each lasting up to a month. Students from other music academies were also invited to apply; admission was based on an audition. Fischer-Dieskau thus taught in the manner of masterclasses: ‘I like working with talented young singers,’ he confessed, "but preferably with a time limit.

He held his teaching position for an unusually long time at his own request. After his regular retirement at the end of the 1991 summer semester, his appointment was extended four more times, each time for one year, until September 1994 - most recently with the special authorisation of the senator.

Even after this, Fischer-Dieskau did not completely give up his teaching activities and continued them on the basis of a teaching contract almost until his death in 2012. The masterclasses ended with public lessons in the theatre and rehearsal hall, today's UNI.T; they also met with great interest from the listening and watching audiences. As everyone could see here, Fischer-Dieskau was strict with the students. In this respect, too, he modelled himself on his teacher Weißenborn: ‘In my opinion, sparing praise characterises a good teacher,’ he remarked.

It should be mentioned that Fischer-Dieskau also conducted, painted and wrote books worth reading. His publishing work began with a work on Schubert's songs (1971) and Wagner and Nietzsche (1974). Many other writings followed. Historical accounts of Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1992) and Carl-Friedrich Zelter, the long-time director of the Sing-Akademie (1997) deal with Berlin topics.

Author: Dr Dietmar Schenk (former Director of the University Archive)