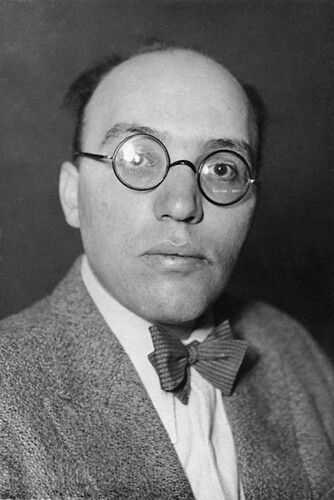

Kurt Weill

The year 2025 should not end without one of the University of the Arts' most famous alumni, Kurt Weill, being included in the newsletter's history column to mark the 125th anniversary of his birth and 75th anniversary of his death. Weill studied with Engelbert Humperdinck at the Hochschule für Musik in 1918/19 and was a member of Ferruccio Busoni's masterclass from 1921 to 1923. Weill's path from loyal Humperdinck and admiring Busoni student to partner of Brecht and the Threepenny Opera is breathtaking, but also consistent in the context of the 1920s.

Kurt Weill grew up in Dessau as the son of the cantor at the local synagogue and left for Berlin at the age of eighteen. He travelled to the not-too-distant imperial capital to enrol at the Hochschule für Musik; in the middle of the war, he dreamed of being able to compose ‘without the worries of conscription’. He was actually spared from military service: Weill studied in Fasanenstraße from April 1918 to July 1919, i.e. for three semesters.

The revolution of 9 November 1918 took place in the middle of this period: the Kaiser abdicated and months of turmoil and unrest gave rise to the Weimar Republic. The “great war” was lost for the German Reich. In the midst of such upheaval, old and new often lie close together. While shots were being fired in the battle for political order in the centre of Berlin - Kurt Weill sympathised with the workers' and soldiers' councils - the former Königliche Hochschule in Charlottenburg was initially still in the slipstream of the events that were taking place. The ‘Royal’ attribute was neatly crossed out on the letterheads used by the secretariat; otherwise, it was business as usual for the time being.

With Engelbert Humperdinck, the new German style had gained a foothold at the university just a few years earlier in its light Rhenish style. Weill was one of the small number of students who were personally taught by the then already ailing ‘head’ of the composition department. ‘I came to Humperdinck by chance,’ Weill told his brother. ‘I had been mistaken for someone else.’ But as early as his second semester, in September 1918, Weill assisted his teacher with the orchestration of the opera Gaudeamus, a comic student opera - the subject matter was already out of time at the time. And Weill himself took Rilke's Cornet, a favourite text of the previous years, not of the ‘new era’, as a model for a ‘symphonic poem’ - now lost.

In addition to Humperdinck, Weill's teachers were Friedrich Ernst Koch, a composer of the Berlin academic school, and Rudolf Krasselt, then first conductor at the Deutsche Oper in Charlottenburg. They were ‘certainly not modern’, Weill wrote a few weeks after starting his studies. But he owed them great technical progress, which he recognised without reservation.

After one semester, he summarised that it was only now that he had ‘got a clue about composing at all’.

I found a document in the University of the Arts archive that reflects the transitional period at the time. Kurt Weill was a member of the Student Council, a newly created student organisation. In July 1919 - around six months after the revolutionary upheaval - things must have got very heated at the university. A student had criticised the advanced age of many teaching staff. Regular retirement at the age of 65 did not yet exist in the imperial era; it had only just been introduced.

It is interesting to see how Kurt Weill behaved in this confrontation between the generations. He signed an appeasing letter asking for leniency for the offender; indeed, he may even have been a driving force behind the drafting of the letter, which was addressed to the directorate of the Hochschule für Musik. ‘The students were painfully affected by the disharmonious and unworthy course of the meeting last Friday,’ it reads. "A seemingly unbridgeable gulf has opened up between teachers and students. Our ardent endeavour now is to facilitate mutual understanding." At the university, as these well-chosen words show, the authority of age had not yet been completely broken.

Weill interrupted his studies at the end of the summer semester of 1919; in the economically difficult post-war period, he had to help support his parents' family and earn money. He took a job as a répétiteur at the theatre in Dessau and then as a conductor in Lüdenscheid. However, the next step in his career took him back to Berlin, to Schöneberg, to Ferruccio Busoni's spacious flat on Viktoria-Louise-Platz. The teacher was allowed to receive his master students enrolled at the Prussian Academy of Arts here for lessons.

Rumours were already circulating at the academy in 1918/19 that Busoni would soon be appointed director. Weill welcomed this prospect, but it did not materialise. When he wanted to resume his studies at the end of 1920, he heard that Busoni would return from Zurich and take over a masterclass - separately from the academy. Through the music writer Oskar Bie, Weill was able to introduce himself to Busoni in person in November 1920 and submit some compositions for examination.

Busoni announced that ‘many capacities’ had applied; it was questionable whether ‘there was still a place left for such young lads’ as Weill. This is what Weill wrote about his first contact with Busoni. Nevertheless, he was accepted. As a result, Weill immersed himself in the atmosphere of Busoni's aesthetic utopia; ‘he let us breathe his essence’, as Weill later put it. The instruction of the small group of just five students began in January 1921.

Busoni learnt to appreciate the young Kurt Weill. The latter - conversely - used the respectful form of address ‘Dear, dear master’ in his letters, full of admiration. Weill was soon commissioned to produce a version with piano of Busoni's Divertimento for flute and orchestra op. 52. Following on from this, Weill composed a divertimento himself. Its last movement was performed in a concert with works by the students at the Sing-Akademie, now the Maxim Gorki Theatre, in December 1922

At the same time, Weill took lessons with Philipp Jarnach on Busoni's recommendation and taught his first pupils himself, including the Greek composer Nikos Skalkottas and the Chilean Claudio Arrau. Weill's reputation as a budding composer was consolidated. His String Quartet op. 8 was premiered in Frankfurt am Main; it was then performed in Berlin in a concert by the November Group, which Weill had joined.

In December 1923, he was awarded a diploma from the Academy of Arts and his studies were now formally completed. Busoni did his pupil the honour of setting a work he had composed for piano. It was a song from the cycle Frauentanz. Seven poems of the Middle Ages for soprano and five instruments op. 10. Busoni died just six months later, in July 1924, aged just 58. Although Weill quickly detached himself from Busoni's personal circle, he was not suited to being a mere adept. However, he held his charismatic teacher in high esteem - as quickly as he himself changed.

Being part of Busoni's class paved the way for a new phase in his life. While attending a performance of Busoni's one-act opera Arlecchino at the Semperoper in Dresden, Fritz Busch, the conductor, pointed out the playwright Georg Kaiser. He was to be recruited as the librettist for a ballet composition Weill was considering. Shortly afterwards, Weill met him at his home in Grünheide near Erkner and an intensive collaboration began.

A new stage began in Weill's short, eventful life, which would later lead him to Broadway in New York during his emigration.

Author: Dr Dietmar Schenk (former Director of the University Archive)