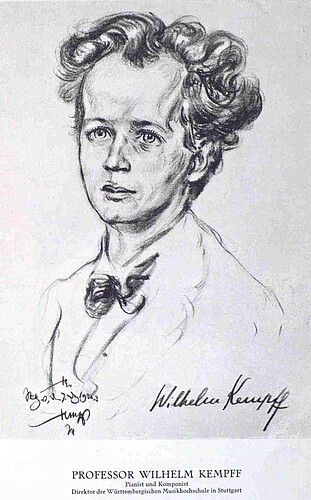

Wilhelm Kempff

On the occasion of the Mendelssohn Competition, which is being held this year in the piano category, we have chosen Wilhelm Kempff (1895-1991) for our university history column. He studied at the Hochschule für Musik, now the music faculty of the UdK, and won the prize twice. Given his illustrious career as a pianist, it is not surprising that he won the prize in piano in 1917. What may come as more of a surprise to some is that two years earlier, in 1915, he also succeeded as a composer - and was thus a prizewinner in two different fields.

Born in Jüterbog on November 25, 1895, Wilhelm Kempff grew up in Potsdam as the son of the cantor at the Nikolaikirche - and at the age of ten knew all the preludes and fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier by heart. His father, who had studied at the Institute for Church Music in Berlin in 1891/92, encouraged his youngest son's musical development, so that he received lessons from Heinrich Barth, the head of the piano department at the Hochschule für Musik, while still at school. As court pianist, Barth took up temporary residence in Potsdam, where he gave piano lessons to the children of Emperor Wilhelm II. The young Kempff learned to compose in private lessons with Robert Kahn, who also taught at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik.

Kempff describes the contrasting atmosphere of the lessons with his two top-class teachers in his memoir Unter dem Zimbelstern (1951). As far as Kahn is concerned, he begins with a scene in which, looking back, he sees himself playing with his two daughters while their father comes home from college, late but whistling cheerfully. Kahn did his pupil the favor of having his friend Karl Klingler play a violin sonata that the young Kempff had composed. This was a prominent performer: Klingler, a pupil of Joachim, is known for the quartet named after him.

Things were different with Barth, who had “a far stricter ‘Prussian’ style”.

Here, the student met those who had their piano lesson before him on the way. “When I climbed the four flights of stairs to his apartment, it was not uncommon for me to come across figures sobbing stunned into their Battist handkerchiefs”. That was “not exactly an encouraging sight for the ‘next person’”. For all his adherence to tradition, Kempff did not conceal the authoritarian traits of the imperial Prussia that shaped him.

Heinrich Barth (1847-1922) is probably only known to very few people today. A pupil of Hans von Bülow and Carl Tausig, he was a grandchild of Franz Liszt. Initially working as a teacher at the Stern Conservatory of Music, he moved to the university in 1871. As a pianist, he was often a partner of Joseph Joachim. By the time he taught Kempff, he had passed the age of 60 and no longer gave concerts himself. As the piano teacher Linde Großmann, who worked at the UdK for many years, has pointed out, Barth is significant because of his influence on the Russian school of piano playing. He was the teacher of Arthur Rubinstein and Heinrich Neuhaus, who in turn was the teacher of Emil Gilels, Sviatoslav Richter, Radu Lupu and many others. Rubinstein describes in his memoirs that he came to Berlin as a child to be introduced to Joseph Joachim, who referred him to Barth.

Robert Kahn (1865-1951), almost two decades younger than Barth, had studied at the Hochschule für Musik with Friedrich Kiel. He knew Johannes Brahms personally; according to his biographer Steffen Fahl, he can be classified as a “late Romantic classicist”. Kahn, the child of a wealthy Jewish merchant and banking family in Mannheim, was expelled from the Academy of Arts in Berlin in 1934 as part of the National Socialist racial policy. Wilhelm Kempff, also a member since 1932, did not publicly oppose this. Kahn emigrated to England.

During the years of the First World War, Kempff had reached the age at which he could regularly enrol at the Hochschule für Musik; he studied from 1914 onwards, again with Barth and Kahn, and completed his training after three years, on July 14, 1917, with a certificate of maturity. Kempff also attended musicology lectures at the university. A Berlin patron, Cornelie Richter, daughter of Giacomo Meyerbeer, supported him financially. After completing his studies, Kempff was drafted into military service. Incidentally, one of Kempff's brothers also attended the university for a semester: Georg Kempff studied singing with Paul Knüpfer, but mainly theology.

The collection of older musical instruments, today's Berlin Musical Instrument Museum, was a “department of the university” to which Kempff was “passionate”. This affinity had an effect on a composition whose premiere took place in 1917 in a “concert with new works” in Berlin's Beethovensaal. The instrument collection was housed in what is now the Kammersaal in the Fasanenstraße building and, if it could not be accommodated there, in the attic. The curator had shown Kempff ancient Germanic luren, “strangely twisted army horns of the Germanic tribes”. Kempff used these in a work that reflects the time of war: Die Hermannschlacht. Prelude to Heinrich von Kleist's drama for male choir and orchestra. However, due to mishaps during the performance, the antiquated instruments were a “sensational laughing stock”, as one newspaper put it. This anecdotal story can be found in Kempff's memoirs mentioned above.

The university knew what it had in its talented and successful student. Kempff was asked to take part in the celebratory concert to mark Heinrich Barth's fifty years of teaching - shortly before his retirement - on June 11, 1921. He played Bach's Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor (BWV 903) and Beethoven's Piano Sonata in C minor, op. 111.

Not too much needs to be said here about Kempff's further career. From 1924 to 1929, he was director of the Württembergische Musikhochschule in Stuttgart. Musically, he belonged to a different world than the one that prevailed at the very modern-oriented Berlin academy after its rigorous renewal in the early 1920s. Nevertheless, an important partner of Kempff's, the violinist Georg Kulenkampff, was working there at the time. Kempff's participation in the summer courses in Potsdam, which were organized by the German Music Institute for Foreigners - led by Georg Schünemann, the deputy director of the university - was one of the main pillars from 1929 onwards.

As a composer, Kempff felt at a disadvantage in the Weimar Republic compared to the New Music movement. This was probably one of the reasons why he became involved with the National Socialists. However, his friends also included Ernst Wiechert, an East Prussian poet with conservative ideals who was imprisoned in Buchenwald concentration camp. Kempff left Potsdam in 1945; his career continued more brilliantly than ever after denazification. One of the highlights was an organ concert in the Peace Church in Hiroshima (1954). His master classes on Beethoven interpretation, which he held in Positano near Naples from 1957 to 1982, are famous. He died there at a ripe old age on May 23, 1991.

No less a figure than Alfred Brendel has warned against underestimating Kempff, who is still held in high esteem in France and Japan, for example. At this point, however, a voice from the University of the Arts should be heard in more detail. Klaus Hellwig, Professor of Piano, was there in Positano when he was young. At a piano recital in Münster/Westphalia, where he grew up, he experienced Kempff for the first time at the end of the 1950s. He remembers Mozart's Fantasy in D minor, which was on the program at the time. "The concert really thrilled me and [...] somehow it also affected me that someone could deal with this music in this way and make it speak as if it had been improvised. [...] This freshness and directness, that you can experience a piece of which you know every note in a new way, like a theater production, was a great experience."

These were Hellwig's words in a conversation with the musicologist Werner Grünzweig, who heads the music archive of the Berlin Academy of the Arts, on the occasion of the acquisition of Wilhelm Kempff's estate. In the winter of 2008/09, the House of Brandenburg-Prussian History in Potsdam presented an exhibition conceived by Grünzweig together with colleagues, which was equipped from this archive.

Author: Dr. Dietmar Schenk (former director of the university archive)