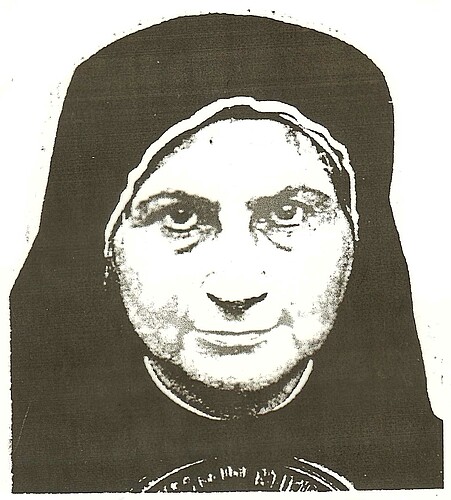

Frieda Loebenstein

This time, Frieda Loebenstein (1888–1968), a pioneer in piano pedagogy, is featured in the university history column. In the 1920s, she played a key role in establishing an innovative seminar for music education at the University of Music, now the music faculty of the Berlin University of the Arts. As a Jew, she lost her position when the National Socialists came to power in 1933. Forced to emigrate, Loebenstein, who had converted to Catholicism, lived as a Benedictine nun in São Paulo from 1939 onwards, where she taught Gregorian chant.

The files of the University of Music contain an ‘agreement’ with Frieda Loebenstein dated 21 December 1932, which was intended to improve her employment status. It was planned that she would work as a ‘full-time’ teacher in future. However, the agreement was subject to approval by the ministry, and this did not happen. After the National Socialists came to power on 30 January 1933 – when Adolf Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor – Loebenstein immediately became the target of racist persecution. A marginal note on the document states in sober terms: ‘This agreement has not come into force.’

The Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur (Fighting League for German Culture), a nationalist, anti-Semitic pressure group of the Nazis, had demanded that the university be ‘cleaned up.’ Frieda Loebenstein was among those listed as people who were to disappear; she is disparagingly characterised as a ‘Kestenbergian, cultural Bolshevik, Jewess.’ It was therefore only logical that the aforementioned contract with her was not concluded. These events ended the brief heyday of the seminar for music education.

Leo Kestenberg, music advisor to the Prussian Ministry of Culture, had made its founding possible in terms of cultural policy. His motto, ‘Education for humanity with and through music,’ corresponded to the music education views of Loebenstein, who was actively involved from the very beginning. Looking back, she expressed her music education credo as follows: ‘I consciously eliminated everything that was purely artistic or aesthetic and began to use music only as a means of inner human education, never as an artistic end in itself.’

This radical statement, directed against the position of ‘l'art pour l'art’, belongs to a time when virtuosity was celebrated, but pedagogical sensitivity was often lacking in the piano lessons that many middle-class children received. This deficit brought counterforces onto the scene. Israeli composer Josef Tal, who had attended the seminar on music education, confirmed that Frieda Loebenstein's ‘congenial pedagogical skills’ were a perfect match for Kestenberg's ‘educational ideal’.

Piano lessons should no longer be training for some kind of performance, but should simply bring joy, awaken vitality and support personal development. Loebenstein incorporated piano playing into an overall concept of music education in which she also attached great importance to ear training. Her ideas were incorporated into the book Klavierpädagogik (Piano Pedagogy), which was published in 1932 in the Musikpädagogische Bibliothek (Music Education Library) edited by Kestenberg.

Frieda Loebenstein's musical and pedagogical inclinations became apparent at an early age. She was born on 16 May 1888 in Hildesheim, the fourth child of a devout Jewish family. Her father was co-owner of the local department store Löbenstein & Freudenthal. As she later reported, she began teaching others music as a teenager. In Berlin, she studied with music theorist and educator Wilhelm Klatte, who brought her to the Stern Conservatory of Music in 1921 as a teacher of aural training. Here she developed into a ‘well-known pioneer of the tonic-do method,’ a teaching method for vocal instruction, and also met the important music educator Maria Leo.

After the Prussian Ministry of Culture regulated private music lessons with a decree in 1925, a seminar for music education was established at the university the following year, which prepared students for the examination for private music teachers in a two-year course accompanying their studies; anyone who wanted to obtain a teaching licence had to pass this exam. According to Kestenberg, the seminar was intended to serve as a ‘model’ for the whole of Prussia. Under the aegis of musicologist Georg Schünemann, Loebenstein took on the teaching area of ‘Introduction to Piano Teaching’. Other teachers included Siegfried Borris, Georg Götsch, Paul Höffer and Charlotte Schlesinger. The seminar also worked closely with Charlotte Pfeffer, who, after training with Émile Jaques-Dalcroze in Dresden-Hellerau, was able to establish the subject of rhythmic gymnastics at the university. A highlight of the seminar work was the world premieres of singspiele for children at the Neue Musik Berlin 1930 event, including Wir bauen eine Stadt (We Are Building a City) by Paul Hindemith.

In the seminar, Loebenstein led ‘practical exercises’ in which music students could take the plunge into educational practice. They learned to teach children – individually and in groups. The lessons were accompanied by careful preparation and follow-up work, as well as scientific research. This instruction was free of charge for the children; the participants came from the poorest backgrounds – they were, according to Josef Tal, ‘our Zille children’. Loebenstein was committed to ensuring that the lessons were given on a continuous basis; the children would simply have been too disappointed if they had had to do without him again after a short time. Over time, a veritable ‘training school’ emerged.

But then, as already mentioned, came the abrupt end of the seminar for music education. But what happened to Frieda Loebenstein after her forced departure? Just a few years ago, this question was still a mystery to many. Thanks to the in-depth research of Eva Erben, which took her as far as Brazil, we can now easily find the answers in her exciting monograph ‘Den Himmel berühren’ (Touching the Sky, 2021).

Loebenstein used the career break in 1933 to make an existential decision that had been brewing within her for some time. Through Romano Guardini, whose lectures she attended for years at Berlin University, and through stays at the Beuron monastery on the Danube, she became attracted to the Catholic faith. In the deep crisis and hardship of the time, many people sought the support and connection that the Catholic Church promised to provide. Loebenstein was baptised in 1934 and joined a community of nuns in Oranienburg; later she moved to the Sisters of St. John in Leutesdorf on the Middle Rhine. She now turned her musical work to Gregorian chant. Together with Father Corbinian Gindele from Beuron, she published the book Der Gregorianische Choral in Wesen und Ausführung (Gregorian Chant in Essence and Practice) in 1936.

In 1939, she realised that she had to leave Europe to save her life. According to their racist stereotypes, the National Socialists continued to regard her as a ‘non-Aryan’. Despite the support of the Benedictines with their worldwide contacts, her path to exile was difficult. Finally, however, she managed to escape to Brazil. As Sister Paula, she was accepted into the community of Benedictine nuns at the Abadia de Santa Maria in São Paulo, where she felt at home. In her secluded monastic life, she was able to continue her work as a music teacher. She remained in contact, mainly by letter, with some people she knew from her time in Germany, such as Paul Hindemith and his wife Gertrud. In 1951, she published another book, Canto Sacro, this time in Portuguese. Over the years, until her death in 1968, she taught Gregorian chant to more than 600 people who did not belong to her monastery, mainly members of religious orders.

Postscript: When I began working as an archivist at what was then the University of the Arts in the 1990s, I received a visit one day from an elderly gentleman. Helmut Köhler, as he was called, had worked as a music teacher in Plauen, Vogtland, for decades and now – after the fall of the Berlin Wall – was returning to the starting point of his professional life for a visit. He brought with him a letter from his lecturer Frieda Loebenstein dated April 1933, which he had kept. During our brief encounter, it became clear how inspiring and formative the work of the Seminar for Music Education had been, and especially Loebenstein's contribution to it. In this sketch, I would like to record and pass on, as far as possible, what Helmut Köhler shared with me at that time.

Author: Dr Dietmar Schenk (former director of the University Archives)